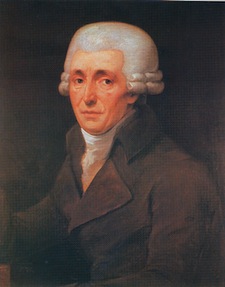

I’m continuing work on the stack of Haydn string quartets tonight (only got through a few last night) as well as a few Duke Ellington discs. The Haydn discs, by the way, are from the Naxos set recorded by the Kodaly Quartet. As with most things Haydn, I tend not to think about listening to something by him until I do, and once I do I am almost always struck by how good his music is. And I wonder why he doesn’t get the same amount of attention as Mozart or Beethoven. While he is often given credit as the inventor (or standardizer) of classical form and style, the virtuosic lyricism of Mozart and the dramatic pre-romanticism of Beethoven is the music that is used to complete the music history story of the classical period. Part of it, I am sure, is because it wraps up into a neater package that way. Haydn had these ideas, and Mozart, Beethoven (and Schubert, etc. etc.) expanded them, then etc. etc… But I imagine another big part is the sheer volume of work. I can literally spend two days listening to all of his symphonies without repeating a single one. The five hours it takes to listen to all the Beethoven symphonies lends itself much more to repeated listening of the whole body of work. So of course I know it much better. But with Haydn, even if I chose the top 20 and got to know them as well as I know the Beethoven 9, I would still have 4/5 of his symphonies to be surprised by! So, for now I think I will let myself enjoy the surprises when I get to them. And I will also let myself remember that if I am looking for some good music that I haven’t heard yet, I can dig into my Haydn collection and probably be pleased.

The Duke Ellington tonight is a nice cross-section of his work. There is a collection drawn from a PBS documentary about him that covers a VERY wide range of his work. Basically, it is like taking a survey course on Duke Ellington. With that disc, you get an excellent sense of who Ellington was as a songwriter / composer. Then there is the mostly amazing ‘Ellington at Newport’ from 1956 which shows Ellington the band leader, and finally ‘Money Jungle’, a trio disc from ’62 with Max Roach and Charles Mingus which shows us Ellington the phenomenal pianist.

‘Money Jungle’ is every bit as amazing as you would expect an album by Ellington, Roach and Mingus to be. The playing, all around, is superb. And in the smaller setting, you hear Ellington’s playing in sparser surroundings. This also means that you hear him filling in more space with his playing, and at times his left hand sounds like McCoy Tyner is sitting in. At times, his playing is HEAVY. And I have heard him voice certain chords like this in other contexts (most notably, in the Ella Fitzgerald ‘Ellington Songbook’ recordings), but in a smaller setting with less players, it sounds like he is giving Mingus a run for his money at times. It sounds like he is giving Max Roach a run for his money… and on top of that, he is giving his right hand a run for its money. The playing is just amazing.

But it is the playing of Paul Gonsalves on the Newport disc that is the standout. After a rough start to the festival, the band sounds a bit warn out at times in the first half or so. But by the time Gonsalves starts his solo during ‘Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue’ you think something amazing has to start happening sometime soon. And it does. The 27 chorus solo that follows is one of the most amazing 6 minutes or so ever captured live on tape. And not to diminish the amazing playing of Gonsalves, but it is also what is going on around him that adds to the moment. Duke egging him on to keep going early in the solo break. Duke and the rest of the band pushing him even further. Then the crowd gets into it. You can literall feel the excitement rise with this recording, and then it ends. Literally, it sounds like Gonsalves has possibly collapsed and is out of breath. It is one of the least graceful endings to a solo you will ever hear, but it is perfect. Gonsalves has given it everything he has got, and when the tune ends, the roar from the crowd (and the time it takes Duke to calm everyone back down to get the concert moving again) shows how just about everyone there realizes how luck they were to hear what they just heard. I’m lucky to hear it. The history of music is lucky that it was caught on tape. I still get chills when I hear this track.