I’ve spent a couple days getting through a couple of box-sets picked out by the girls. Mostly it has been a busy few days, and I’ve also been trying to stay away from the computer a bit more this weekend. So – this will be a short (though still overdue) posting.

The two box-sets were: Davitt Maroney’s excellent performances on harpsichord of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier (with the Art of the Fugue and the Musical Offering thrown in) from Harmonia Mundi, and the Wergo 5-CD digital recordings of Conlon Nancarrow’s studies for player piano. Kind of a pre-piano / post-piano combination.

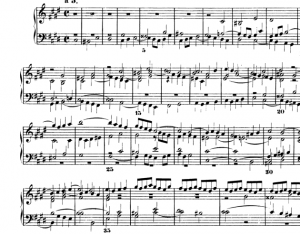

The Bach of course is such a standard in piano repertoire and practice, that it can be hard sometimes for pianists to think about the differences between their instrument and the one that it was written for. While the most common instrument that is thought of from Bach’s time is the harpsichord, and performances of the ‘48’ on that instrument are the most common, it isn’t out of the question to hear these works also on organ or even lautenwerk. But on harpsichord, the lack of a wide dynamic range for single notes – and the focus on texture and multiple voices for creating changes in dynamics – is usually much more clearly heard. Fugues get louder as more voices enter. The C-minor prelude from book 1, with it’s two voice continuous 16th note texture that eventually thins out to basically a single voice followed by dense chords and rapid melodic flourishes. The dynamics here come from the number of notes sounding at any one time and their orchestration, and on the harpsichord these changes to texture are quite dramatic.

The Nancarrow studies come about well over 200 years after the Bach works, and as a body of work is just as significant. The works were composed on the piano rolls themselves as Nancarrow punched holes into the paper, having measured out horizontal space as time, and calculating where the pitches he wanted needed to be punched. This liberation from both the pianists hands and the written mensural notation led to all sorts of interesting manipulations that were often based still on compositional concepts from Bach’s time and earlier. Canons are especially prominent, though they may be well outside the reach of a single pianists two hands. And they may also go through transformations that would be difficult for a human reader to comprehend, especially in respect to time. Time intervals are stretched and contorted, sometimes accelerating according to the laws of physics rather then the subdivision of the beat. And like Bach, where the popular dance music of the day often influenced some of the form and content of the Preludes in the Well-Tempered Clavier, the influence of jazz and boogie-woogie piano playing appear in Nancarrow’s works.

When I first came into contact with the player piano studies, I actually remember seeing a light-bulb go off in my head. The idea of time being measured in distance rather then simply as divisions of a measure seemed so intuitive! Our system of rhythmic notation suddenly seemed so restrictive to me! And once this occurred to me, my thinking in electronic music also greatly changed. Time and music could have pulse, and it could also disappear. Like pitch, intensity and any other musical parameter, rhythm too could be dynamic when it is thought of as a portion of time rather then just the division of a measure. It still surprises me how simple this approach can seem, and how complex the results of it can be.