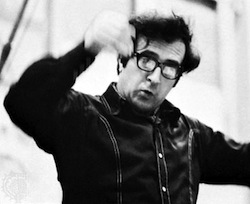

So tonight I am finishing up the Brendel Beethoven discs on Vox Box. I mentioned to my friend Katherine (who is an amazing pianist) that I LOVE that in this set, Vol. 1 Disc 1 starts with the ‘Hammerklavier’. On top of that, the whole of Vol. 1 (two discs) is dedicated to the late sonatas. Scoff at Vox Box all you want – this set is intended for collectors who know what they are looking for. Young Alfred Brendel, and they are throwing one of the most difficult works of Beethoven at you as disc 1 track 1.

I have the ‘Appassionata’ on right now (and I’m ripping disc 6 of 15 at the moment). And wow – I forgot how good these performances are. The accelerando in the last movement is thrilling, and played so clearly. Just amazing.

The recordings themselves though are a bit noisy. Tape hiss is audible, and this makes close editing of the movements feel choppy (end note, QUICK fade out of hiss, then onto the next movement). Other then that though I have nothing to really complain about with these recordings.

And my favorite aspect of them is that for the most part Brendel takes all the repeats. This is really a pet-peeve of mine – it drives me crazy when a performer omits a repeat from a performance. I still remember the first time I heard Brahms’ first symphony WITH the repeat in the first movement and I couldn’t believe how big of a difference it made! It is somewhat known that Brahms actually told people that he thought the repeat could be omitted ‘once the piece is known’, but I think that is actually a huge mistake. WIth the first symphony, the repeat back to the beginning has an extremely jarring effect on the listener. It makes the c minor of the first symphony even more c minor! It is darker with the repeat, and as a result when you reach the stunning B major triad at the beginning of the development THAT moment is so much brighter. Without the repeat is smooths the piece out… with it, and it is much more dramatic.

Beethoven’s music (and most works from the classical period) need the repeats to work structurally and rhetorically. Repetition is so crucial to musical understanding, and Beethoven used repetition better then just about any composer. Beethoven used the structural patterns of the classical period on so many levels as well, and took this aspect of the classical period and manipulated it (and how listeners perceive repetition) in the most dramatic way possible. His understanding of how melodic fragments could be referenced within the music for the listener is probably the quality of Beethoven’s composing that I think makes him truly unique. The connections he creates by taking advantage of how a person builds up memory is truly masterful. At the same time – it is this aspect of Beethoven’s writing that I think Brahms misses the point on most of all. The sweeping gestures that Brahms created in much of his music are a bit too long to be remembered as a whole for most listeners (but they are often discovered by music students who study his work!). If there is any reason why Brahms’ 1st ISN’T Beethoven’s 10th, it is in this difference. However, I think this is something that Brahms did pick up on in the end of his life. His pieces that are the most Beethoven-ish are his last sets of piano works (op. 116. 117, 118 and 119). Hmm… if I get done with these Brendel recordings tonight, I think I need to grab those late Brahms pieces next…