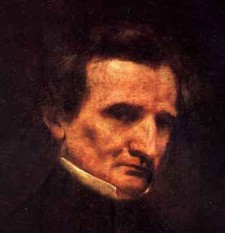

After playing the Beethoven violin sonatas a bunch today, Celia really seemed to be getting into violin playing. I put on some of the Paganini violin / guitar duets after breakfast (wafflepalooza for dads) this morning and Celia really liked those as well. She also learned the word ‘violinist’. So I went downstairs and dug up the rest of my Paganini for tonight. And as I started to listen to more and more of his work (I have a stunning amount of Paganini CDs it turns out) I started chuckling to myself more and more. There really are time in his music that are just simply ridiculous. Like – how in the world did anyone think of putting that many notes down at one time for a single instrument to play ridiculous. Like Bugs Bunny playing Liszt with both hands and ears ridiculous… and that is when I made a connection. Celia (and Mira) are going to love this music. It is fun, flashy and just a little silly sometimes. At others, it is operatic. Sometimes very serious, and sometimes SOOO serious that it becomes comic again. Music historians have often compared the early romantic period virtuosity of Paganini and Liszt. It broke away from the classical restraint that so much music of the late 18th and early 19th century sometimes had, and pushed the virtuosic into another realm altogether. So it is no wonder that this music would show up in Looney Tunes, which both of my daughters have taken a serious liking towards. And the fast, joyful playing of Paganini’s violin, I imagine, doesn’t strike Celia as too different from the music she has been hearing in those cartoons.

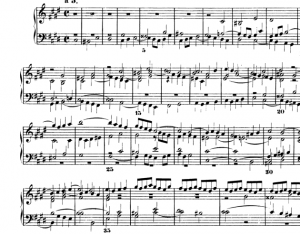

Of course, as a musician I also find this work fun from the technical standpoint. It really is pretty crazy at points, and having tried to play some of it I appreciate how amazing any of these players are. Even more astounding to me is that, even in Paganini’s music that seems to be just for light entertainment (the violin and guitar duets, or the guitar quartets), I’m surprised at the demands placed on the players. And while so much of the writing is flashy and showy, it is also very musical. Technically it is amazing, but that is only after it is amazing musically.

This is a point of frustration to me with so many composers today, especially in academic circles. There seems to be a need (or expectation) that music should be challenging and difficult (to play as well as listen to). And I certainly think new work should push the art along. But often what I hear that is challenging isn’t that engaging. There are composers who explore complex approaches to composition but want the work to sound un-complex (then why do it???) and there are others that want to write something that just isn’t playable. Just because we can compose out of time, subdivide rhythm into impossible ratios and pitch into minute distinctions doesn’t make the music good. However, if the music is good and requires that such demands are made, then that is a different story. In Nono’s string quartet ‘Fragmente Stille, An Diotima’ there is a wonderful chord that happens about 2/3 of the way through the piece, and I know that Nono knew it. It lasts longer then just about anything else in the work (including the long rests), and when I was doing an analysis of the piece I was surprised to see how it was built. Within the piece, it is a moment of clam beauty. On the page, it is built with quarter-tone dissonances which, from the sight of it, should be jarring. But within the context of the whole work, it is a shimmering moment of beauty that had to happen. I have no way of knowing for sure how he came up with this chord, but it is the perfect one. And it is challenging to play and tune. It is technical complexity that comes from a musical need, and I see a connection between this and the demands Paganini placed on his performers. To make it worse, the result of these passages needs to feel effortless. Virtuosic performers can make it sound like their fingers know where they are going, but virtuosic musicians will make it sound like there is simply no other way to do it.